You don't need to be a banker to put together a logical theory of banking and money. You just need to lay all the clues into an interlocking order. We will try to do that in this article.

This becomes a story of banking and the creation of modern money. Printed money is not part of this story, nor is the valuation of money.

Money is used ubiquitously. Everyone has some familiarity with it. Nonetheless, we need to find some clues and make a few observations before we can get a sense of where money originates.

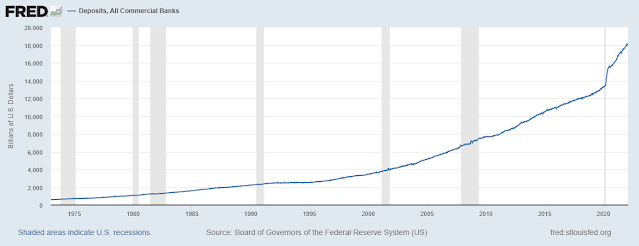

The first observation we have about modern money is that the supply of it is increasing. Because money is stored in banks, we can add all the deposits in the nation to see that this is happening (Figure 1).

The second clue we have is that I can lend you money. Of course, I must first get money from someone else before I can do that. We can see intuitively that money gets passed around or, in a single word, reused.

Yet another clue is that banks make loans by assigning to a borrower an account preloaded with money. This newly assigned account is identical to all other accounts loaded by depositors who first earned money. A side question arises here: "Who was the owner of money placed into the borrower's account?"

This is a side question but very relevant. We will take a moment to consider it.

From the first observation, we know that the money supply increases. From the second clue, we know that money can be reused, which is not an increase in money supply. The question itself may be misleading. There may be no previous owner. The money preload itself may be newly created money.

The puzzle that we really want to solve is how money is created.

Let's assume that money is created when banks make an account preload. That accounts for the observation that the money supply increases. Of course, this money would be available for reuse until somehow it might be caused to disappear.

If it is this simple to create money, it must be simple to destroy money. That thought is nothing more than a logical extension of the probable life expectancy of anything that mankind might create.

Extending the Puzzle into Money Destruction

If we begin thinking about the destruction of money that we have previously assumed into existence, we would be expanding the scope of the puzzle, by a lot. Yet, destruction seems to be a necessary part of the money supply mechanism. We haven't yet any clues that destruction of money is possible except that we know intuitively that paper money can be destroyed by burning.

We aren't going to burn up bank accounts so what mechanisms can we find that might result in the destruction of money?

We can observe that borrowers are always asked to return borrowed money. More formally, a loan agreement is usually written. We should be able to safely assume that a return of borrowed money to the bank would 'uncreate' money.

We might have the complete answer to our puzzle. We have a coherent mechanism for the creation and destruction of money, but it is based on assumption following assumption. Can we make it robust in an accounting sense?

It seems that we can, but management of the money product is a necessary part of the story.

There should be no difficulty in accounting for creating money. The bank took a signed loan agreement in conjunction with preloading a borrower's deposit account. We can observe that two distinct types of wealth have been created, both subject to standard accounting methods.

Now we throw a wrench into our 'uncreating' assumption by assuming that the borrower defaults on the loan. It seems like this would leave money permanently present in the economy, unless there is another destruction mechanism in place just for this event. There is such a mechanism, a management mechanism, and it works like this:

Assume that the borrower has spent his preloaded money so that it comes to be owned by third parties and unavailable for repayment.

Further assume that banks are regulated with a requirement to absorb loan losses. Because money left the bank, loan default results in a loss of money that must be absorbed by the bank. This forces the bank to write down a deposit account owned by the bank. Thus, the bank needs to account for both a loss of wealth attributed to the loan document and a loss of wealth attributed to a deposit write down. In this case, both wealth and money would be destroyed by the rule of regulation. *

In one sense, upon default, banks are forced to revise history. Beginning with money creation, history records money supply increases. This increase is recognized repeatedly until, finally, the bank is forced to report the loss and recognize it on its balance sheet, thus reversing history. What seemed to be a history of money creation is rewritten to be a history of money reusage.

Strict regulation keeps money creation under control, preventing the money product from becoming worthless due to oversupply.

Conclusion:

The theory presented in this article assumes that money creation occurs when banks preload a deposit account and simultaneously accept a signed loan agreement (bond). This action creates two units of wealth (money and bonds). Both money and the linked bond persist in the economy until the bond is retired. When bonds from the originating bank are retired, two units of wealth (money and bonds) disappear from the macroeconomy. The disappearance of money depends upon strict adherence to accounting rules that require disappearance.

Notes:

* I don't know for certain if any existing government regulation actually forces this accounting method onto retail banks.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Mike King for his series of articles and comments. The first of these articles, "Defining Money", can be found at:

https://stochasticpress.com/economics/2021/10/26/defining-money/

The theory expressed here departs from the theory found in King's series.

(c) Roger Sparks 2022

Roger,

ReplyDeleteI'm thinking in terms of construction or farm loans. The preloaded money in the loan account feels like a "promise" to the borrower. It's like the bank is saying, "We'll take a risk on your proposal. We'll transfer emblems of our support for you to the lumber yard or the seed company in order to get you going. At the end of the season when you sell your houses or your crops, we'll take the money back which you borrowed, plus a little more. We'll use that 'little more' to cover other risks we are underwriting and keep the whole process rolling down the track."

The bank is lending money, but that money is merely a promise to cover the costs of building or farming until the newly created housing or crops are realized. (Somewhere in the bank, there has to be "real" money deposits, doesn't there? Money that was deposited by savers who had been productive and had actually produced real wealth?) Those newly created houses and granaries filled with wheat are real wealth and are traded for money, part of which goes back to cover the loans taken out. The profit, if there is one, is not destroyed with the retired loan or bond. That, or part of it, is put back into the bank as interest and used as a foundation for further lending.

How's that? I'm I getting it?

It still feels like to me that much of that lending and borrowing activity is a gambling or risk taking enterprise with rules that keep it from spinning to far out of control. Money, when it stopped being sea shells, or pigs, or gold coins became an object of shared belief between the people who had faith that it represented the potential to become something they desired.

We better hope we, the entire world, continues to believe in money and the hope it represents.

I still am wondering how the government feels about tens of thousands of lending institutions creating money, money which is backed by its "full faith...etc." Is the Fed really in control of the money supply? It doesn't feel like it.

Still thinking.

Josh

Hi Josh,

DeleteI have a newer post on this blog site. Now I would respond that your bank lender is giving you 'tickets'. Money as a 'ticket'.

So, I would agree that the bank is giving me money, thereby becoming a partner in my business.

Then we look at what the bank is doing. We wonder where does the bank get ALL THESE TICKETS that are being loaned? It indeed seems that money/tickets are being created somehow.

I fear that it is far easier to create tickets than to recover/vanish them.

Roger